Shelf Life

Author Edmund White reflects on the pleasures of books — writing them, reading them, keeping them, and how they shape our lives.

WORDS BY EDMUND WHITE, PHOTOGRAPHY BY LEVI MANDEL

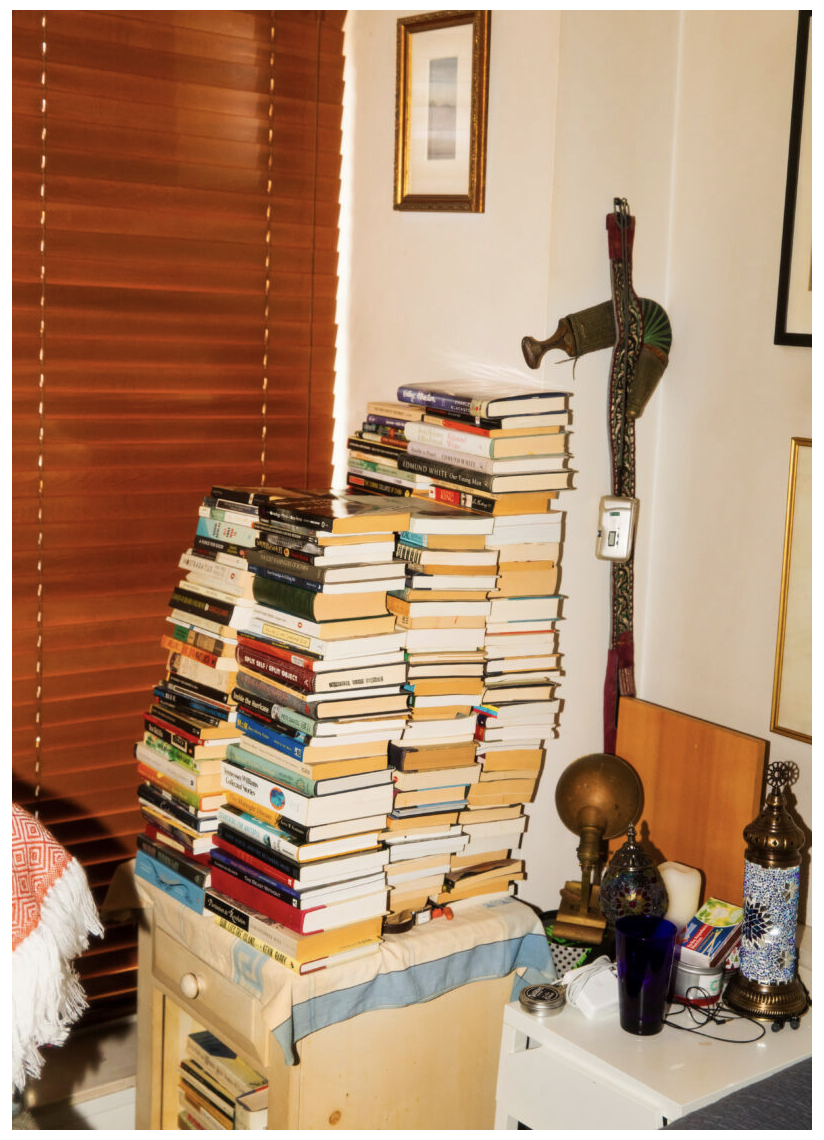

ONCE MY BOYFRIEND and I were having loud sex at 2 a.m. immediately above my landlady’s bedroom. She came upstairs and rang our bell, furious, but my roommate told her I was piling up my books. We moved our games to another room. The next day I sent her a dozen roses with the message, “You’ll be glad to know, Books has moved on.”

I guess that excuse came to mind because we’ve always lived with hundreds of books, spilling out on the floor, piled in stacks everywhere, “arranged” in double rows on every bookshelf — and never alphabetized.

Some poor soul lived with us for a week trying to make some order out of them, which soon reverted to chaos. It’s easier for us to buy a new volume of the same title than to locate the original. An archeologist could tell from these dupes which books we actually reread.

Three huge piles by the window are art books — which are so high they obscure one of our best paintings, an Ethiopian work of marching Communists with big black eyes, red flags, and green uniforms, done by the court painter for the new conquerors of the ousted Haile Selassie.

I have the original outsize printing, a folio edition, of Jean Genet’s “Querelle of Brest,” a gift from a French photographer friend. I also have, somewhere, an original publication with gilded edges and stamped gold art nouveau lilies on the cover of Pierre Loti’s “Madame Chrysanthème” (a novel that is the basis of the opera “Madama Butterfly”). Collectible editions, however, are for bibliophiles, not readers. Give me a hundred paperbacks stuffed into a wooden crate rather than one pristine first edition. By the way, I’ve discovered over the years that an edition signed by the author is more valuable than an unsigned one, but a book that is inscribed to you if you are a nobody is less valuable unless the author signs the book to another celebrity (Sartre to Beauvoir). I’m not famous, but I was delighted when the philosopher Michel Foucault dedicated a book to me en toute complicité (in all complicity).

Gary Shteyngart has a funny novel, “Super Sad True Love Story,” set in the future in which young people are nauseated by the smell of books, which must be disguised by pine spray in order to be tolerable. Bibliosmia means the intoxicating odor of good books. I just learned that librocubicularist refers to someone who reads in bed.

Libraries are peculiar things. One of the most beautiful is in Paris that belongs to the venerable French Academy, the Bibliothèque Mazarine, with its green-shaded lamps and classic chairs. The austere rooms are home to thousands of incredibly rare books. I once visited an aristocratic family in Genoa whose eighteenth-century ancestor was a book collector and had the idea to buy the last illuminated manuscript of a title (Dante) and the first printed version of the same title. He had all the books bound in different colors, which was pretty but followed no logical method. A grad student had to be brought in to digitize the entire collection (“Erasmus” is green, second shelf, third volume in). We had to wear white gloves before handling a page. Since book collectors are happy to possess a rarity but don’t bother to read it, the illuminated manuscripts were pristine, in glowing colors, never touched by daylight.

“Bibliosmia means the intoxicating odor of good books.

I just learned that librocubicularist refers to someone who reads in bed.”

The most beautiful library I’ve ever seen is in the Catholic monastery of Einsiedeln, in the snow-covered Swiss mountains. Many books there are from the ninth century when the abbey was founded. The room is cold, white, and radiates out from a bible in four languages. Perhaps the most beautiful library I’ve never seen, except in photographs, is at the Waldsassen Abbey in Bavaria, Germany, built in 1724-6 by magically inspired local craftsmen, in carved linden wood and swirling, decorative plasterwork — a rococo masterpiece.

These days no one buys used books. As a result, you might find unlikely titles in a writer’s library — old, worthless bestsellers — the things publicists have mailed out, not actual choices. Somehow it feels a bit fascist to throw these ugly ducklings out, to purify the breed for the discerning eyes of visiting litterateurs.

Hardcover books — or just actual books — are better than e-books because with real books, you know that funny remark or quote you loved was about a third in at the bottom of a left-hand page. Or you know how much more you have to read. Imagine my dismay while reading “The Good Soldier” — Ford Madox Ford had used up the whole plot, the plane was landing — and I was only halfway through! Of course, that’s the genius of the book, but a bit bewildering to the common reader.

As a child, I was so frustrated I couldn’t read yet. In cruel wonder, my sister would point to a sign and exclaim, “You really don’t know what that says?” Once I learned how to read, I said to myself, “What a wonderful golden key has been placed in my hand!” I probably didn’t really think that, but I like to imagine I did. I was a snobbish, obnoxious boy who fancied himself too good for children’s classics like “Treasure Island.” Instead, I had my heart set on reading a translation of Anatole France’s “Thaïs,” which was kept under lock and key behind the librarian’s desk. I had seen its white calfskin binding and gold deckled pages and knew it was about a woman who has an affair with a very pious Desert Father (an early Christian hermit) — just my speed. I took my case all the way to the mayor’s office until the librarian finally relented and ceded to my request.

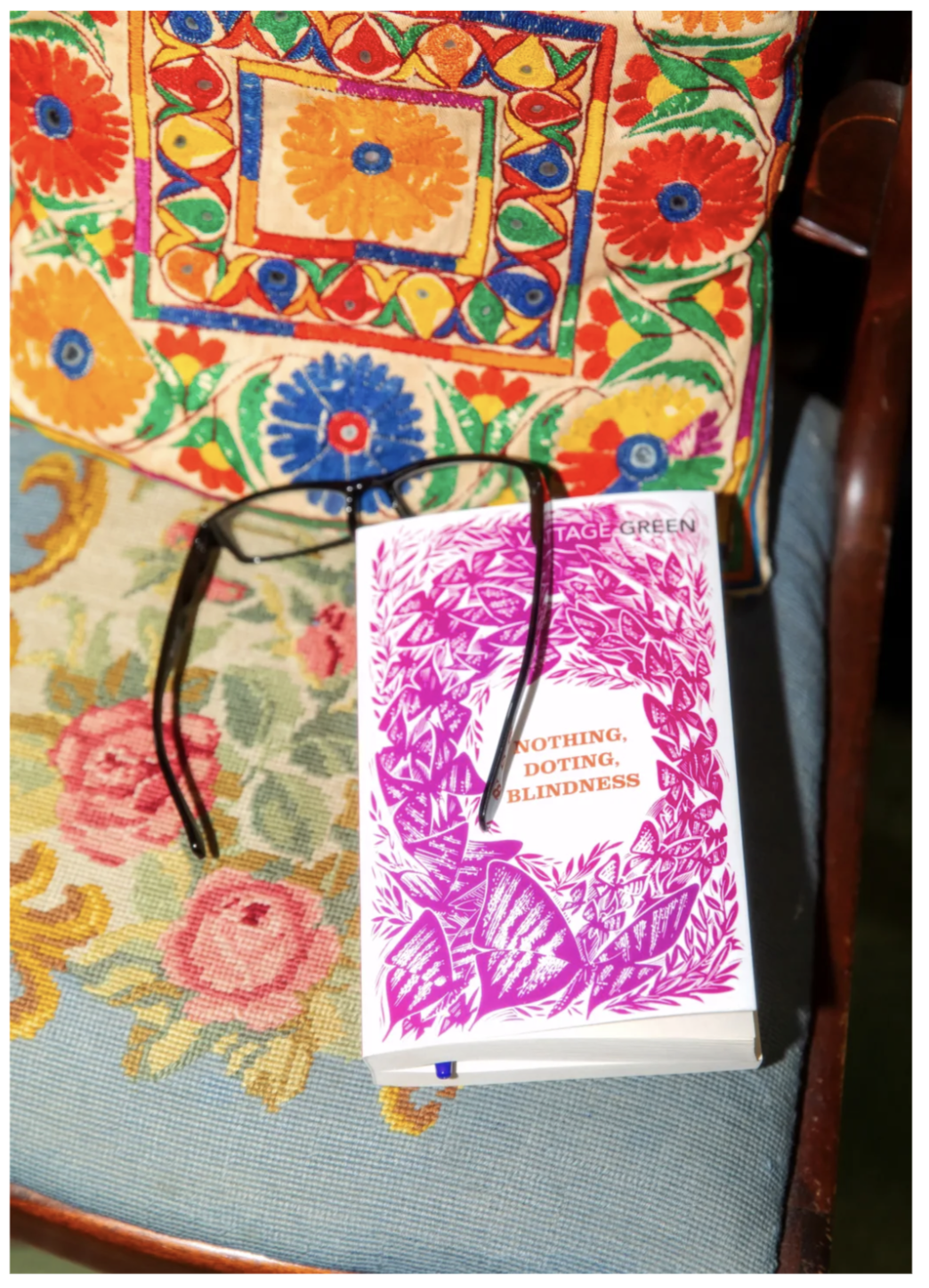

My greatest pleasure was to wander through the open stacks and discover little treasures hiding behind modest covers. That’s how I was drawn to Henry Green’s novels with the intriguing gerund titles like, “Loving, Living, Party Going” and my favorite, “Nothing” (what part of speech is that?). I didn’t understand their sly wit as a child, but I reread “Nothing” every year with undiminished merriment. As a kid, I was drawn to their stylish titles and covers, all matching. Similarly, I read Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Marble Faun” because it was a pretty nineteenth-century copy. Although I claim to be indifferent to the look of books and care only about the content, I was obviously more of an aesthete as a boy.

I can remember the books I received as a boy as gifts. In fourth grade, a friend gave me a biography of the lost dauphin of France, Marie-Antoinette’s son, who may or may not have survived in the United States (a grifter in “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” pretends to be the dauphin in jeans). My stepmother gave me the complete poems of T.S. Eliot: “For Eddie, who is 13!” Oddly the poems that seemed mysterious in the 1950s now appear to be utterly limpid.

If I look through my hundreds of books, I see many reminders of my biography of Proust and another one of Rimbaud, many of the best, expensive French editions (“Les Pléiades”) of writers I’ve written essays about (Jean Giono, Colette, Jean Cocteau) and those non-French writers who’ve interested me (Knut Hamsun, Ivan Bunin, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki).

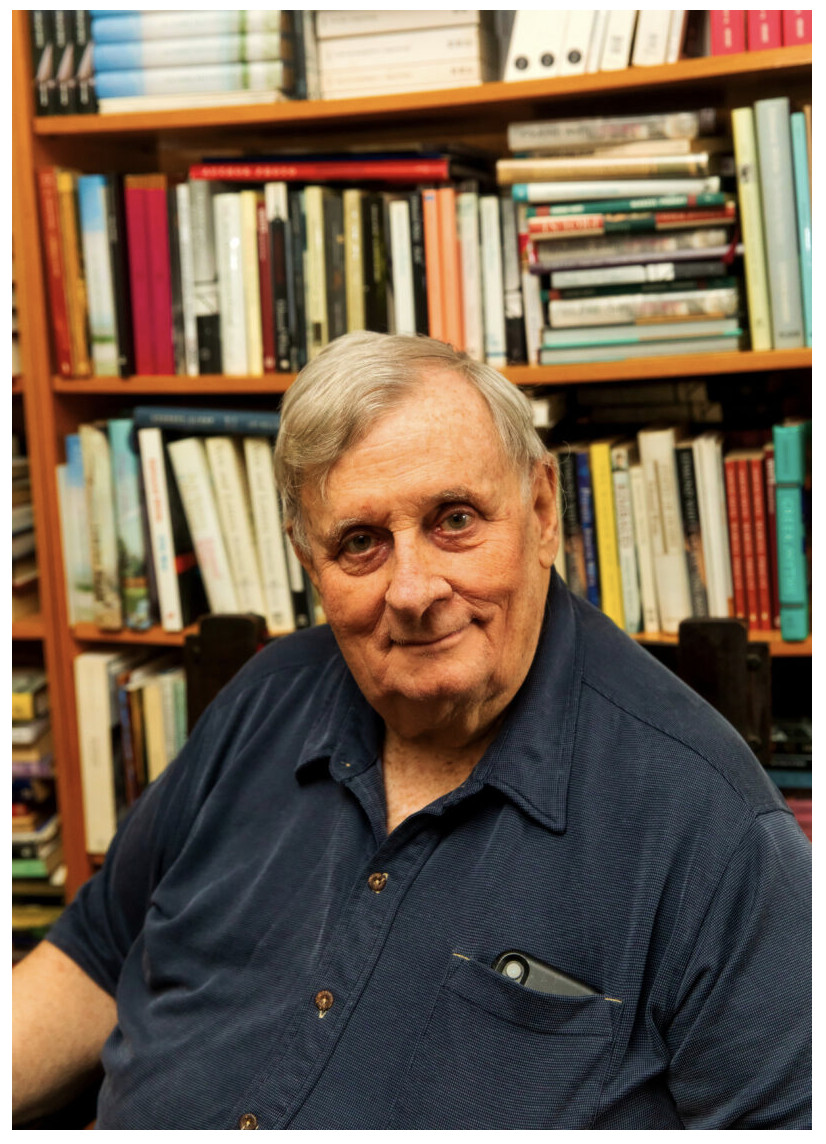

Reading is still so absorbing; it’s an old man’s pleasure. At 83, it is the best way to travel to other cultures and periods. I love “The Tale of Genji,” the “Iliad,” “The Princesse of Cleves,” Dante, Sophocles — they all invite us into other realms, other psychologies, and other material cultures. Often, I get lost in my reading and only come out of total absorption at dawn. It’s the same disorienting exhausted feeling that I had in my 20s — coming out of a disco in the morning and melting into the crowds of office workers heading for the subway, me in my dirty T-shirt, them in their coats and ties and skirts and high heels. As a novelist, I find that other books often inspire mine, but I’ll never identify which is which; in my latest book every character is a plagiarist.

A photograph of the author in the 1970s by Barbara Confino.